AI Doesn't Kill Jobs. It Reveals Them.

Five days of intensive AI-assisted work, a research experiment on 12 language models, and the question that kept coming back: what does human complexity actually mean when a machine can reason?

Five days. No weekends. Multiple nights past midnight. I don't usually work like this, but a few personal events pushed me into a kind of focused sprint I haven't had in a long time. At the center of it: AI agents, research pipelines, and a question I kept running into whether I wanted to or not.

Why do I still have to explain the same things twice?

The Pattern That Kept Showing Up

Every developer who has worked seriously with AI agents long enough will recognize this. You set something up, it works, you move on. Then a few sessions later, the same gap appears. You define a context, a constraint, a preference - and somehow it needs to be stated again. Not because the model forgot. Because the session did.

I had a task running for over 60 minutes. Multiple sub-agents spawned. Coordinator, implementer, researcher, reviewer - the whole pipeline. The output was genuinely good. But at several points I still had to step in. Not to correct the logic. To supply context that I had already supplied.

And that got me thinking about the AI-kills-jobs conversation in a different way.

What 'Replace' Actually Means

The argument usually goes: AI can now write code, analyze documents, generate reports, make decisions. Therefore, people who do those things are at risk. The math seems simple.

But when I look at what actually happened over these five days, the picture is more specific. The AI handled things I would describe as structured complexity well - tasks with clear inputs, known patterns, defined success criteria. It handled them faster than I could, and often better.

What it did not handle without friction: judgment about what matters, decisions about priorities that depend on context I hold implicitly, and the kind of iterative correction that comes from understanding why something was done a certain way, not just what was done.

That gap is not a flaw to be patched. It is the actual shape of the tool.

The Experiment

One of the projects from this week was BMAS - Blind Multi-Agent Synthesis. The premise: take 12 different language models, give them the same 45 prompts across three domains (technical, regulatory, and strategic), and measure how much they agree with each other. Not which answer is correct. How similar their outputs are.

The hypothesis: on precise technical questions, models converge. On ambiguous strategic questions, they diverge. Divergence signals either genuine uncertainty in the domain or hallucination. Convergence signals reliability.

The results confirmed this directionally. Technical domain: BERTScore mean of 0.811. Regulatory: 0.820. Strategic: 0.814. The cosine similarity - measuring structural semantic overlap - was notably lower across all domains, averaging 0.491. Meaning the models agree in substance more than in framing, which is itself an interesting finding.

The full dataset, paper, and analysis are at github.com/homeofe/BMAS

The GPU Problem and What It Actually Represents

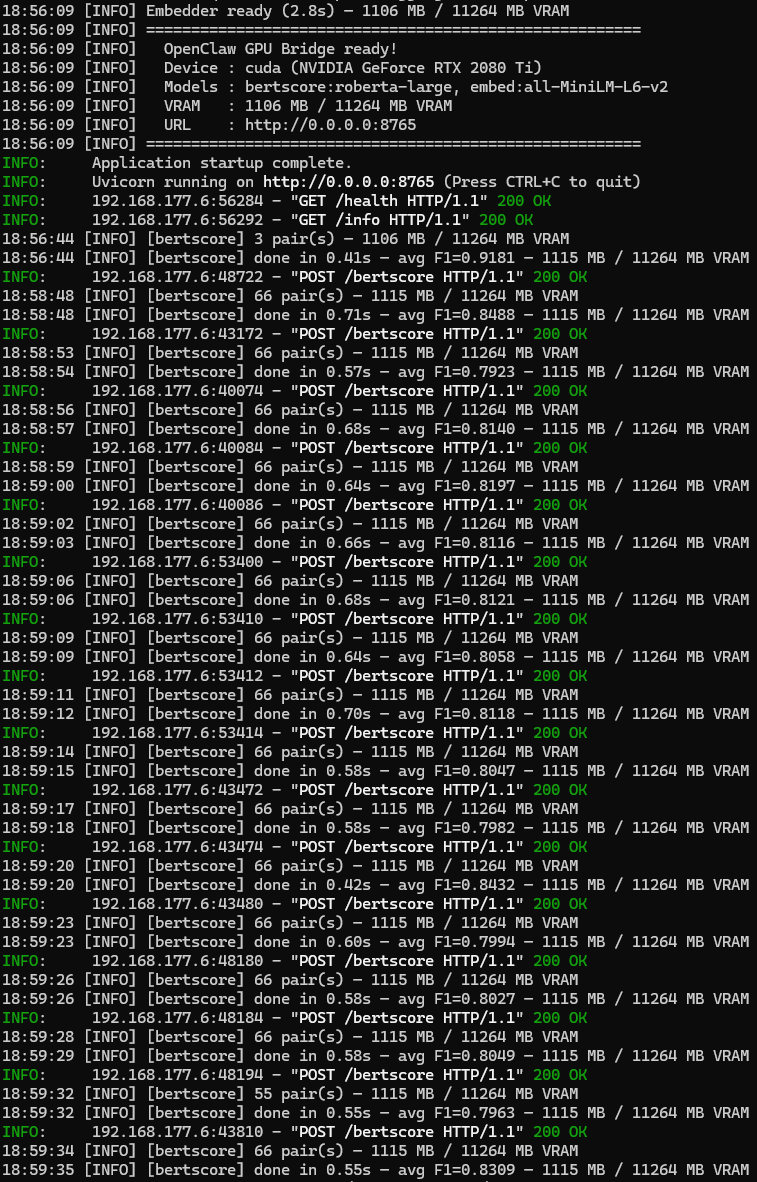

Running BERTScore on CPU for 45 prompts across 12 models - 66 pairwise comparisons per prompt - would take roughly 3.3 hours. That is not a pipeline. That is a waiting room.

So I built something to fix it: openclaw-gpu-bridge. A small FastAPI service that runs on a machine with a real GPU, exposes endpoints for BERTScore and semantic embeddings, and lets the orchestration logic stay on the main machine. CPU for control, GPU for compute. The GPU bridge handles the heavy inference. The local process handles everything else.

After the bridge: 66 pairs processed in ~0.6 seconds. Full 45-prompt run under 5 minutes. The math is straightforward but the principle matters - not every problem needs to run where you are. Some problems run better somewhere else, if you build the right interface.

Getting Started

Start the GPU service on the machine with the GPU:

cd openclaw-gpu-bridge/gpu-service

pip install -r requirements.txt

uvicorn gpu_service:app --host 0.0.0.0 --port 8765Install the plugin:

npm install @elvatis_com/openclaw-gpu-bridgeConfigure and call:

import { GpuBridgeClient } from '@elvatis_com/openclaw-gpu-bridge';

const client = new GpuBridgeClient({ serviceUrl: 'http://192.168.1.x:8765' });

const scores = await client.bertScore({ candidates: [...], references: [...] });

const embeddings = await client.embed({ texts: ['hello world', 'hi there'] });GitHub: github.com/homeofe/openclaw-gpu-bridge npm: @elvatis_com/openclaw-gpu-bridge

Back to the Actual Question

What level of human cognitive complexity can AI actually reach?

I think the honest answer, based on this week, is: more than most people admit, and less than the loudest voices claim. The structured parts of knowledge work - the parts that can be decomposed into steps, verified against criteria, executed consistently - those are largely solved. Not perfectly, but well enough to change the economics of doing them.

The parts that remain genuinely hard for AI are the parts that are also hard for humans to explain. Knowing when a constraint matters and when it can be relaxed. Reading a situation and deciding that the real problem is one layer up from the stated one. Choosing to stop and ask instead of continuing with a reasonable but wrong assumption.

Those things are not mysterious. They are skills. And like most skills, they are learned through experience in a specific context, not through generalized training. Which, as it turns out, is also true of humans.

A new hire knows their domain. They do not automatically know how this team works, what this company cares about, or why that particular decision was made three years ago. That knowledge is built through exposure, repetition, and feedback. AI is not different in this respect. It needs context. It benefits from specificity. It improves with iteration.

The difference is scale and speed, not kind.

What That Means Practically

For me, after five days: AI does not replace the judgment. It compresses the execution. The work that used to take a day of focused effort - write the code, test it, fix the edge cases, document it, review it - that work now takes a morning, if the framing is right.

The framing is still mine. The judgment about what matters is still mine. The decisions about when to push and when to stop are still mine.

Whether that counts as AI killing jobs depends entirely on how you define the job. If the job is execution, yes, the economics change. If the job is knowing what to execute and why, no, the demand for that has not decreased. If anything, it has increased, because now you can act on it faster.

From Insight to Protocol: BMAS and AAHP

BMAS started as a measurement project. But measurement without action is just observation. The findings - that AI models converge on structure more than on framing, that divergence clusters around ambiguity, that some models consistently behave as outliers - those findings shaped something practical.

AAHP (AI-to-AI Handoff Protocol) is that practical layer. It defines how sequential AI agents hand off context to each other without losing the thread. If BMAS asks "how well do AI agents agree?", AAHP answers "how do we make them collaborate reliably anyway?"

The connection is not incidental. You measure behavior to understand failure modes. You design protocols to contain them. That is the same loop that exists in every engineering discipline - observe, model, build.

AAHP is open source and available at github.com/homeofe/AAHP. The BMAS dataset and paper are at github.com/homeofe/BMAS.

Not macht erfinderisch

I did not build the GPU bridge because I had a plan for it. I built it because the alternative was waiting three hours per run, and I had better things to do with three hours.

That is how most useful tools get built. Not from a product roadmap, but from a specific friction that becomes intolerable. The friction here was compute time. The solution was routing the heavy work to a machine that could handle it, over a simple HTTP interface that costs almost nothing to build and nothing to maintain.

There is something worth sitting with in that. We talk a lot about AI needing massive infrastructure - data centers, specialized hardware, enterprise contracts. And for training, that is true. But for inference, the story is different. The GPU in the machine on my desk handles BERTScore for 66 text pairs in 0.6 seconds. The full pipeline that would have taken 3.3 hours on CPU finished in under 5 minutes.

I started in IT on a 286 with 25 MHz. Today, the smallest phones have more raw compute than that machine had by several orders of magnitude. The hardware barrier for this kind of work is not where most people think it is. You do not need a data center. You need the right interface.

That is what openclaw-gpu-bridge is. A small, focused interface between the machine that orchestrates and the machine that computes. Open source, MIT licensed, 22 files, 11 kilobytes.

GitHub: github.com/homeofe/openclaw-gpu-bridge npm: @elvatis_com/openclaw-gpu-bridge

I don't think that's a comforting message for everyone. But it is an honest one.